A review by Mercy Oluwanisola Akintola.

The first time someone close to me died, it was my paternal grandmother. According to those around her, there were signs that she was preparing to leave. Her skin started to glow, and she had deep, intentional conversations with her children reminding them to be kind and patient with their father, her husband. Another sign was that my youngest cousin, her last grandchild, turned his back to her for three days before she passed. None of these signs made sense to us at the moment; they only became clear a few hours after she died.The adults in my life said she knew she was going to die, so she prepared everyone the best way she could. If I had to compare the story of her last days to any film, it would be My Father’s Shadow.

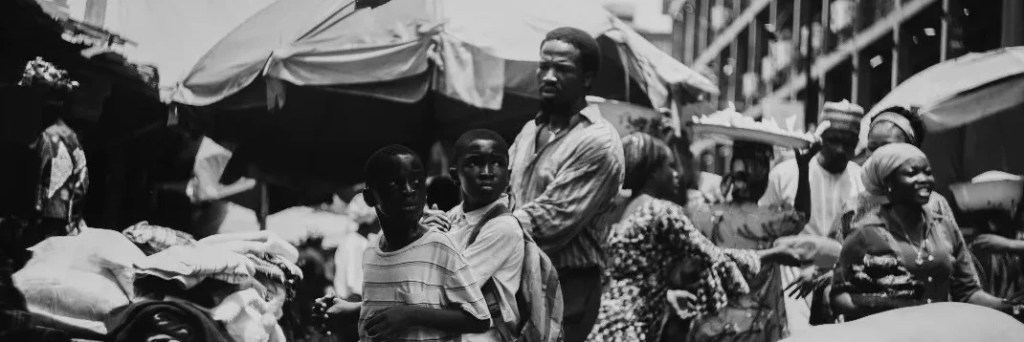

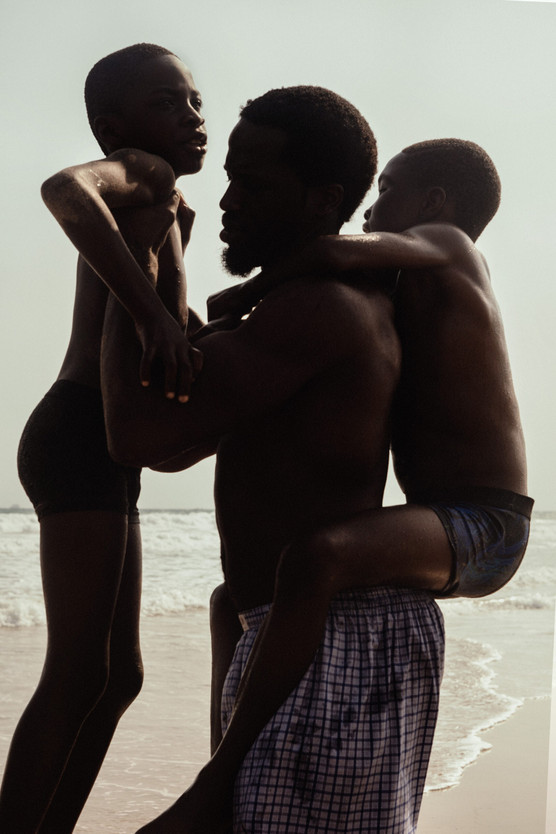

The film begins with two brothers simply being boys, playing with paper action figures, eating together, talking and laughing freely. You didn’t need to be told they were brothers; they showed it. Their father calls them into a room, and seeing how hesitant they are for him to leave again, he decides to take them to Lagos. For the first time, they get to know the world outside their small, familiar environment, experiencing life through their father’s eyes. They witness the parts of Nigeria that feel ordinary yet extraordinary once you really look at them: the way ants move together, the crabs walking along Ajah beach, the long petrol queues that only appeared during fuel scarcity or Christmas, the ever-present religious fanatic in every situation, and the way so many Nigerians lean on “God go do am” as a solution to everything. It was relatable in a way only Nigerians truly understand, but told clearly enough for anyone to feel the story.

Cinematography

The cinematography reminded me of old cassette films my parents and their friends watched before CDs became popular: the warmth, the grain, the slow movement of the camera. Pure nostalgia.My favorite scene was at the beach. In that moment, there was no politics, no struggle, just a father and his sons, living, learning, and being present with one another.My favorite line in the film was when one son confronted his father about never being around. The father replied, “Everything you sacrifice, you just have to make sure you don’t sacrifice the wrong thing.”For me, that was a wake-up call, a reminder that in all my striving and ambition, I must not forget to check up on my people, to be present, to love while I can.

I wasn’t born when the Abiola ’93 election happened, but I felt the pain and anger Fola felt. It reminded me of every election I witnessed as a child, the way my parents made sure we all stayed home throughout election weekend to keep us safe. It reminded me of corrupt Nigeria: missing ballot boxes, chaos, confusion, and all the characteristics that make up a Nigerian election.The film ends with Fola, the father, trying to get his children home safely to avoid any trouble caused by the election results. They are stopped for no reason by an agitated military officer who orders their father sitting in the back seat to get down. That scene hit hard, because 30 years later, Nigerians still experience the same brutality, only now it comes in a different font

called SARS.The film shows how much Nigeria has evolved, and yet how little has truly changed on a larger scale.

Another detail I appreciated, which we rarely see in Nigerian films today, is the authentic celebration of life during mourning. In many recent films, when someone dies, everyone wears black, which does not reflect how we actually honour our dead. Here, the film captured that balance: yes, we are sad, but we don’t have to look sad. And the hymn “A o pade leti odo” instantly transported me back to my grandmother’s funeral mass.

Characters

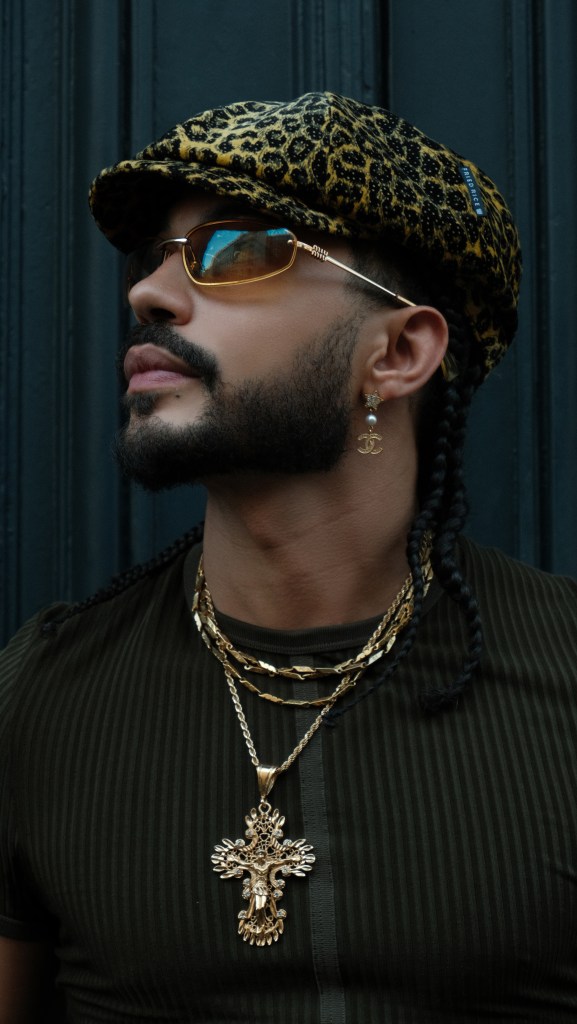

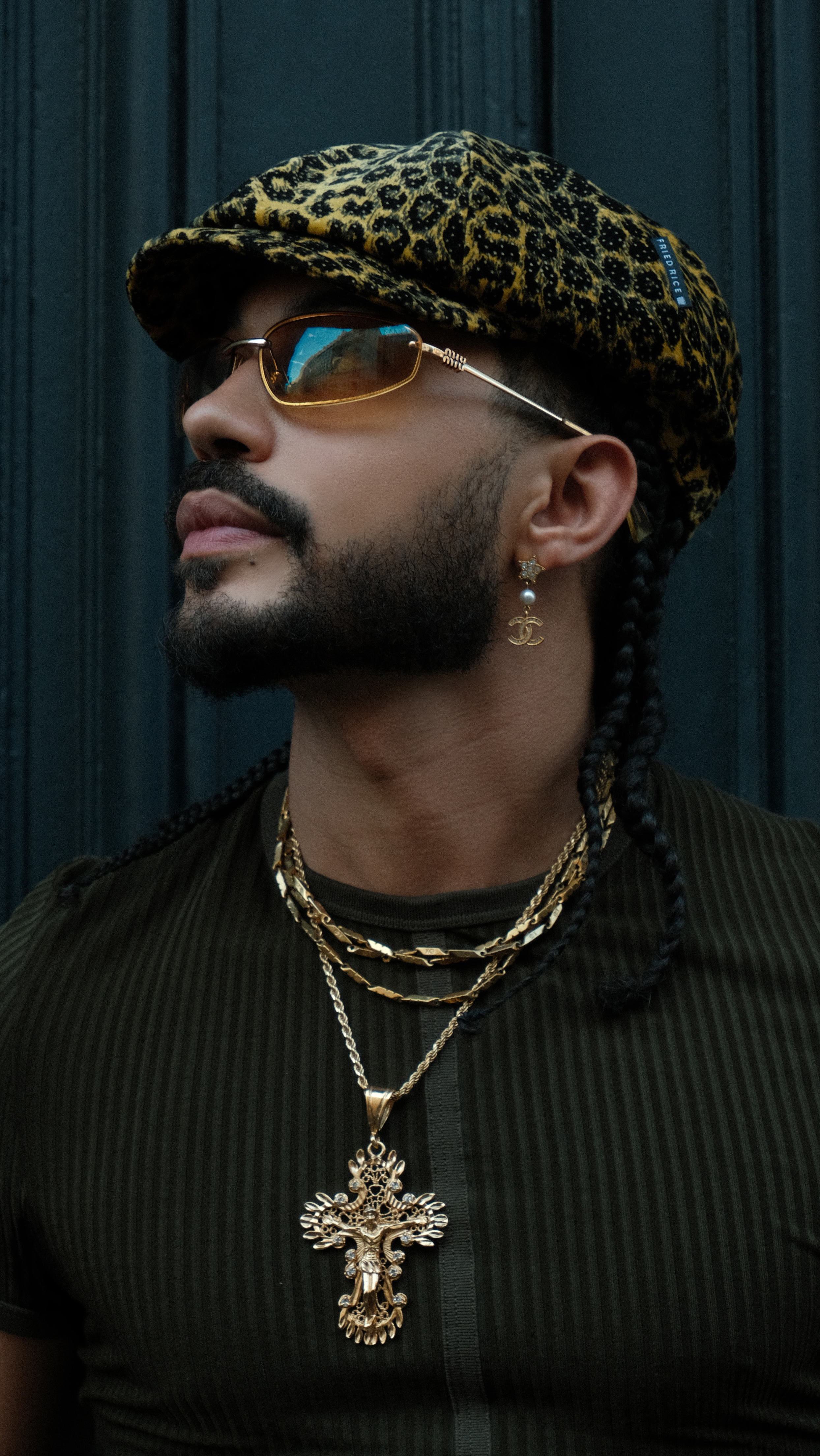

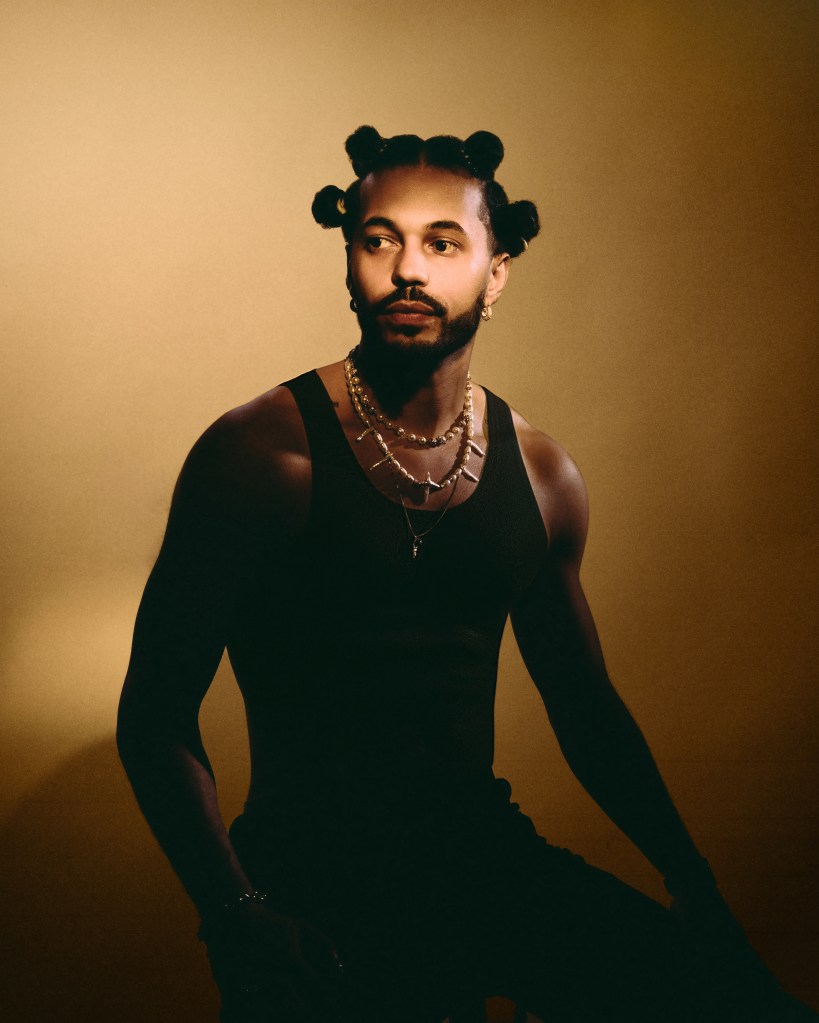

The acting was strong. The side characters played by Greg Ojefua, Patrick Diabuah, and the talented Ụzọamaka who are some of our best actors in Nigeria, so I expected excellence, and they delivered. The boys, played by Godwin Egbo and Chibuike Marvelous Egbo, were convincing. I immediately compared them to two of my friends who are brothers, they had real chemistry. Later, when I learned they are brothers, it made sense. If you’re a cinephile, you could notice some inexperience, especially in moments where they accidentally looked into the camera, but for their first film, they did well. I look forward to seeing them grow.

The woman,my favorite character,played by Wini Ẹfọ̀n, was outstanding. She appeared briefly, said nothing, yet delivered everything her character needed to. No crumbs left.And now to the main actor, the man of the hour: Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù.There is no doubt that Ṣọpẹ́ is a magnificent actor, but in some of the dialogue, the British accent tried to jump out the same way my h factor tries to jump out when I’m speaking fluent English. In a few lines, it felt like he was announcing his dialogue. If you’re not obsessed with films or Nigerian speech patterns, you might not notice it at all.

Direction

The direction Akinola Davies took made sense. The film carried an indie softness, and considering how different Nigeria is today compared to 1993, the world-building must have been challenging. Yet, they managed to take us back. His attention to detail was clear, he gave us exactly what we needed, without leaving gaps or over-explaining.

The storytelling by Wale Davies and Akinola Davies is one for the books. It raises the bar not just for Nigerian storytelling, but for African storytelling. My Father’s Shadow feels like the beginning of our stories being told properly, and I can’t wait to see what African cinema looks like in five years.

I feel sad that those of us in the diaspora only get to watch it at film festivals. I hope it lands on streaming platforms next year because I want to watch it again and again. I would rate it a solid 5/5. When someone asks me for a Nigerian movie recommendation, I will shout My Father’s Shadow before they finish their sentence. This story is inspiring, not just because I love films, but because the storytelling itself blew my mind.